A case for precise insulin dosing in type 2 diabetes

Author: Nimet Maherali, Ph.D.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/nimet_maherali

Medium: https://medium.com/@nimet.maherali

This is the story of how I helped my dad with his diabetes. After reversing my own pre-diabetes and drawing on research from circadian rhythm biology, I made a recommendation to my dad that went against his doctor’s advice – to reduce his dose of long-acting insulin and make up for it with short-acting insulin. This turned out to be the linchpin that helped him achieve lower blood sugar levels.

Previous attempts to manage my dad’s diabetes

My dad has had type 2 diabetes (T2D) for 30 years, and previous attempts to modify his lifestyle and take him off insulin had proven ineffective. In fact, these previous efforts typically led to higher levels of blood sugar. After these failed attempts, he went back on insulin, taking a long-acting form once a day and a short-acting form after meals.

An observation

I was previously diagnosed with pre-diabetes and used a combination of time-restricted eating (TRE) and limited refined carbohydrates to reverse the condition (story published here). For several years my dad had refrained from eating during the evenings (a form of time-restricted eating), and I wondered why he wasn’t receiving greater benefit from this eating pattern. Research into the relationship between circadian rhythms and feeding/fasting cycles has shown that eating in a circadian fashion (i.e., eating during the day and fasting at night) has metabolic benefits [1]. It occurred to me that my dad’s body was exposed to insulin around the clock, as he took the long-acting form of insulin. This could make the body believe it was constantly in a fed state, which could undermine the impact of time-restricted eating. Based on this reasoning, I proposed that he reduce his dose of long-acting insulin and use short-acting insulin after his meals to compensate.

Going against medical advice

At the time, this was counter to his doctor’s advice, which was to take more long-acting insulin. My dad had already tried taking more long-acting insulin, and the increased dose did not help his overall blood sugar levels. His diabetes had also progressed to a point where he was about to need injections into his eyes to prevent diabetes-related blindness. He was motivated to make a change, and had an intuition that his doctor’s suggestion might not be correct.

Steps to ensure safety

When I suggested that my dad reduce his dose of long-acting insulin, we wanted to make sure that he produced enough of his own insulin to safely implement this change. He therefore had a test to check his c-peptide levels, which were in the normal range. This confirmed that he still produced enough of his own insulin; we were pleasantly surprised by this result.

Implementing the change

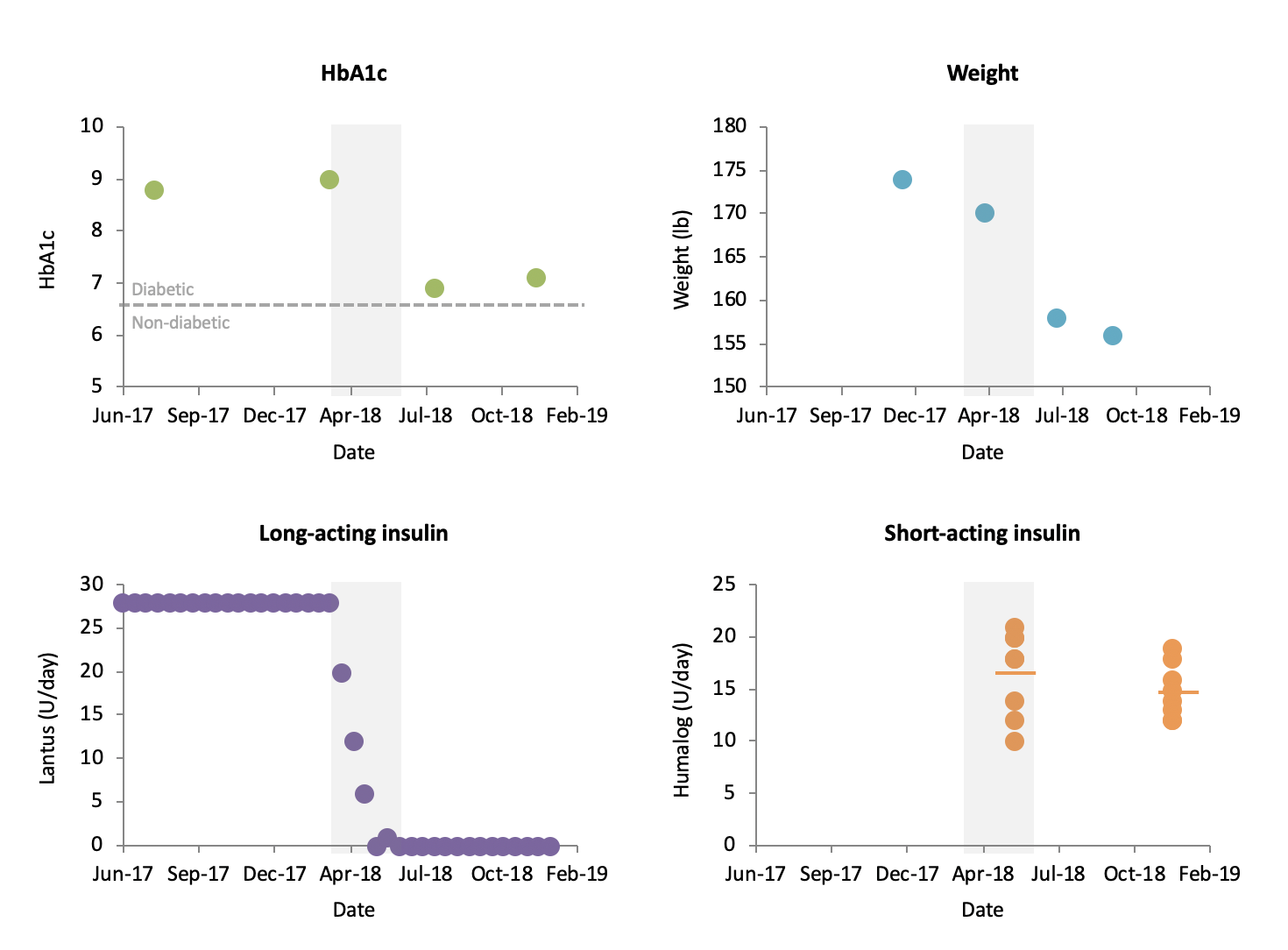

Over the course of two months, my dad gradually lowered his dose of long-acting insulin, from 28 units per day to 6 units per day (Figure 1). During this time, he lost weight quickly and his eating habits improved. Once he reached 6 units per day, we made further attempts to optimize his eating habits and insulin dosing. We kept strict records of his diet, his blood sugar, and his doses of insulin. He tried eliminating long-acting insulin completely, which revealed trouble with fasting blood sugars (the dawn phenomenon). Based on this result we tried doses between 1 and 6 units at different times of day. Ultimately, my dad opted to take no long-acting insulin and instead use an herbal supplement to improve his fasting blood glucose levels. He is happy with this, although I would have preferred he find a dose/timing of long-acting insulin to prevent the dawn phenomenon, since the supplement he is using has not been tested in trials.

Results

My dad no longer takes long-acting insulin. He uses metformin, herbal supplements, and Humalog (at meals) to control his blood sugar levels. Ultimately, he did not need to increase his dose of short-acting insulin. About three months after he stopped taking long-acting insulin, his HbA1c was 6.9 (down from 9.0 at the last reading). This was the lowest HbA1c he has had since being diagnosed. He also lost 14 pounds. Since this time, he has maintained healthy eating habits (eating three meals a day of roughly the same types of food), is following time-restricted eating more rigorously, and has maintained the lower HbA1c and weight. His daily insulin needs are less erratic, and lower than they were before (from 17U to 15 U daily average of short-acting insulin), which may reflect some reversal of the underlying insulin resistance.

Figure 1. Summary of results: HbA1c, weight, daily dose of long-acting insulin (shown as two-week average), and daily dose of short-acting insulin (10-day measurements shown at two time-points). Shaded area represents period that long-acting insulin was reduced.

My dad is thrilled with the results. His last two doctor visits showed no deterioration in his eyes, and he is thrilled to no longer pay for long-acting insulin. He has also started coaching his brother, a newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic, on healthy eating habits (time-restricted eating, fewer refined carbohydrates), resulting in his brother losing 20 pounds over a few months.

Discussion

Reducing the dose of long-acting insulin seemed to be the linchpin in lowering my dad’s blood sugar and weight. Although it is not clear whether these benefits resulted from improved eating habits or the lower doses of long-acting insulin, I argue for the latter. This is because when he increased his dose of long-acting insulin, he had hypoglycemia and ate higher-glycemic foods to make up for the low blood sugar. I believe that lowering the dose of long-acting insulin made it easier for him to improve his eating habits.

This effect has been noted by diabetes expert, Dr. Richard Bernstein, who has said that doses of long-acting insulin are typically too high, lowering blood sugar to an extent that it drives food intake (typically carbohydrates) [2].

The results seen in my dad are consistent with the biology of insulin. Long-acting insulin is designed to replace basal levels, which prevent blood sugar from rising during fasting. Short-acting insulin is used to cover blood sugar after a meal. A study in type 2 diabetics using an insulin pump in connection with a continuous glucose monitor showed that more insulin is needed after meals than is needed during fasting [3]. Thus, the strategy of using less long-acting insulin and more short-acting insulin after meals might prove beneficial for a broad range of type 2 diabetic patients.

Summary and next steps

Based on my own experience with pre-diabetes and my understanding of insulin biology, I suggested that my dad treat his diabetes using methods that contradicted the advice of his doctor. Weaning himself off of long-acting insulin provided numerous health benefits, including reduced HbA1c and weight. As a next step, I would like to reverse my dad’s insulin resistance by using a combination of time-restricted eating, limited refined carbohydrates, and precise insulin dosing using a closed-loop system. I hope his insulin resistance can be reversed, and that he can maintain normal blood sugar levels through lifestyle modifications and minimal medication (e.g., metformin, and no insulin injections). The changes we saw in my dad are beyond what we had hoped for, and highlight the critical role of precise insulin dosing in managing type 2 diabetes and potentially reversing the underlying insulin resistance.

References

- Hatori et al, 2012. Time-Restricted Feeding without Reducing Caloric Intake Prevents Metabolic Diseases in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Cell Metab. [Pubmed] [Full text]

- Bernstein, 2007. In My Opinion: There is No 24-Hour Basal Insulin. Diabetes Solution Website. [Full text]

- Bally et al, 2018. Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery for Glycemic Control in Noncritical Care. NEJM. [Pubmed] [Full text]

Disclaimer

Please check with your medical provider before making changes to diet and insulin regimen.